Effects of Russia – Ukraine impact for 2023 crop year

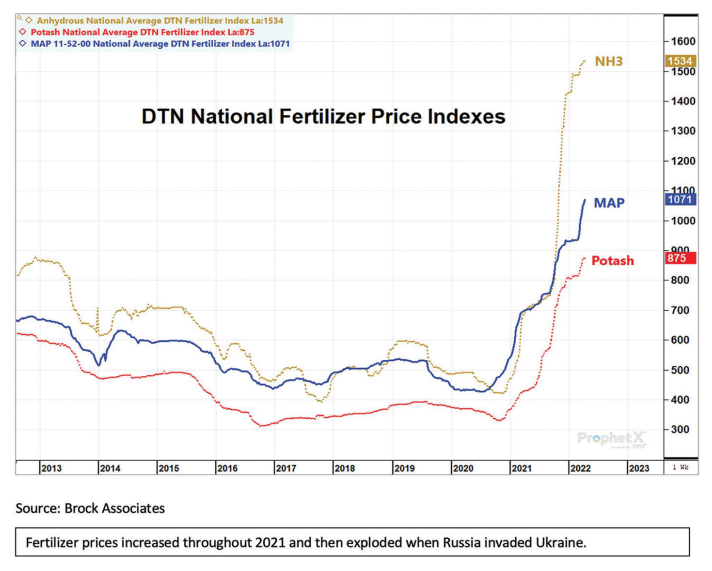

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year ignited commodity markets and exploded fertilizer prices. But in terms of directly affecting the Midwest farmer, no immediate changes were made in planting intentions or fertilizer use. Inputs had been purchased; ground had been prepared. But that could change when farmers start formulating their needs for next year’s crop early this fall.

This spring, Midwest farmers profited from skyrocketing grain and oilseed prices. With corn prices setting records around $8 per bushel this spring, farmers swept out their bins. At the end of April, “I sold more corn at $8 per bushel this week than I have in my entire life,” said Cal Dickson, chairman of Hertz’s Grain Marketing Committee, who has been with Hertz as farm manager and real estate broker since 1984. Even on new crop, prices have been through the roof. “We’ve been selling incrementally as the market has moved higher. The new crop prices locked in this spring are the highest ever available at this time of year,” added Kirk Weih who has been managing farms since 1979.

On the negative side, Russia’s invasion has caused a spectacular rise in fertilizer prices which were already high compared to a year earlier. However, spring fertilizer costs and supplies have had less effect on the 2022 crop because most imported fertilizer was already in place at U.S. dealers before Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24.

And many farmers had already purchased their fertilizer needs. “Fortunately, we locked in our fall fertilizer needs in August and were able to get 98% of it applied with good fall weather,” Weih explained. However, farmers are starting to worry about input costs for next year’s crops and what their profit picture might look like.

What’s Ahead

“Even if the conflict is solved tomorrow, there will still be long-term effects,” noted Cortney Cowley, senior economist at the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank. The World Bank estimates crop fertilizer prices to rise about 70% in 2022 before falling slightly in 2023 [from atmospheric levels].

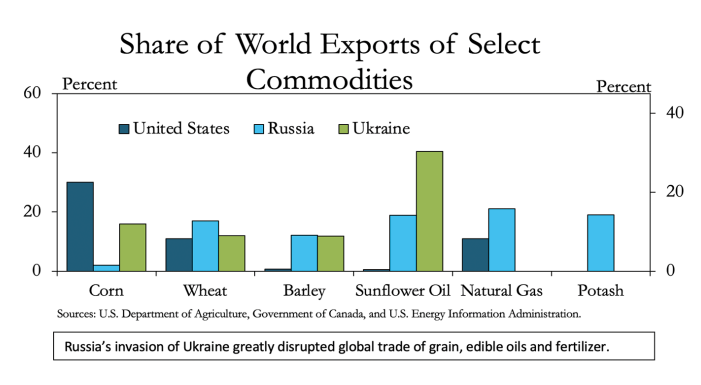

Russia is the world’s leading nitrogen fertilizer exporter with 21% share of global trade. Sanctions reducing that source, as well as other bottlenecks such as the pandemic lockdown in China (another major nitrogen fertilizer producer) and logjams in global transportation has caused nitrogen fertilizer prices to explode. In addition, with the European Union eliminating natural gas imports from Russia, the E.U. will likely switch the main ingredient of nitrogen fertilizer over to heating homes, increasing its need to import fertilizer.

While the U.S. produces most of the nitrogen fertilizer it uses, we import 12% mostly from Trinidad and Tobago, and Canada. U.S. farmers will have to compete in the world market with farmers from countries such as Brazil which imports almost all of its nitrogen fertilizer needs. “We need nitrogen fertilizer every year to maintain high yields. It may be harder to get the form of nitrogen we want and prices will likely remain high for 2023,” advised Hertz farm manager Dickson.

The high cost of nitrogen could also switch some acres of corn next year to soybeans which fix nitrogen from the air and are cheaper to produce, but also have a lower return per acre.

Potash fertilizer supplies will feel a greater impact because Russia and Belarus produce more than a third of the global potash and account for 40% of global potash exports. With countries eliminating trade with Russia and Belarus via sanctions, that puts the squeeze on the remaining potash suppliers to meet demand. The U.S. imports 93% of its potash needs. The bulk of that (83%) from Canada and about 12% from Russia and Belarus.

While nitrogen must be applied every year, potash and phosphorus applications may be dialed back for the short term without impacting yields. “Many of our managed farms have built up the level of potassium and phosphorus in our soils over the years; it may be time to draw on the benefit of these higher levels for a year or so until fertilizer availability and price settle down,” explained Dickson.

On the plus side, commodity prices are expected to stay strong as countries that relied on Ukraine and Russia for grain and oilseeds have to find new sources. The Middle East, north African and Southeast Asia will be searching to find new countries to import grain from, noted Kansas City Fed economist Cowley.

Prices still have upside potential if the war continues, said Dickson. Demand remains high. “When people are hungry, they’ve got to eat. There are no other substitutions,” Dickson explained. “However, if the Ukraine war ends, we could see corn prices drop $1.50 per bushel and soybeans drop $2 to $3 per bushel.”

Ukraine is often called the breadbasket of the world. Farmers there are expected to get some cropland planted this spring. However, the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) in April estimated that Ukraine agricultural production would be cut by one-third.

The saying “high prices cure high prices” has been true in the past but high prices may linger a little longer than the last commodity bull market. “2022 is not the same as 2013 when high commodity prices were short-lived,” said Cowley. “We outproduced ourselves after 2013 with four to five years of bumper crops and there were more substitutes around (wheat and barley for high-priced corn).” Today, the weather has not been that favorable, especially in the Plains states for bumper crops. “And we have other uses for corn and soybean oil -- for fuel,” Cowley added. “It’s hard to know how high commodity prices will go with demand so strong and supply so uncertain. In the U.S., the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will not affect our food security but it will affect prices.”

Long-term, though “I’d rather have three years of $5 per bushel corn than one year of $8 corn. Demand will be affected and around the world, farmers will produce more, and eventually prices will fall,” Dickson advised.

Caution Moving Forward

“From talking with farmers, there is a sense of caution out there now. With rising input costs, one farmer told me he needs to double his working capital,” Dickson reported. “There is a little more uncertainty and uneasiness,” said Dickson. A farmer who typically would trade for a new planter is waiting. The war in Ukraine is another uncertainty added on to rising interest rates, a stronger dollar, inflation and supply chain issues that is making farmers a little more cautious.